Marquis Childers builds accessibility, opportunity, and trust across West Michigan communities

From classrooms to blueprints, Marquis Childers advances accessibility, community voice, and opportunity through education, advocacy, and grassroots leadership.

In a sixth-grade class at Reeths-Puffer Middle School, students huddle around tables covered with Legos, cardboard, and markers. They’re not building just for fun. They’re designing playgrounds, parks, and storefronts, all with accessibility in mind.

Leading the conversation is Marquis Childers Jr., an accessibility advocate with Disability Network West Michigan (DNWM). He recently spent time at the school discussing disability awareness, inclusion, and what it means to design spaces that work for everyone.

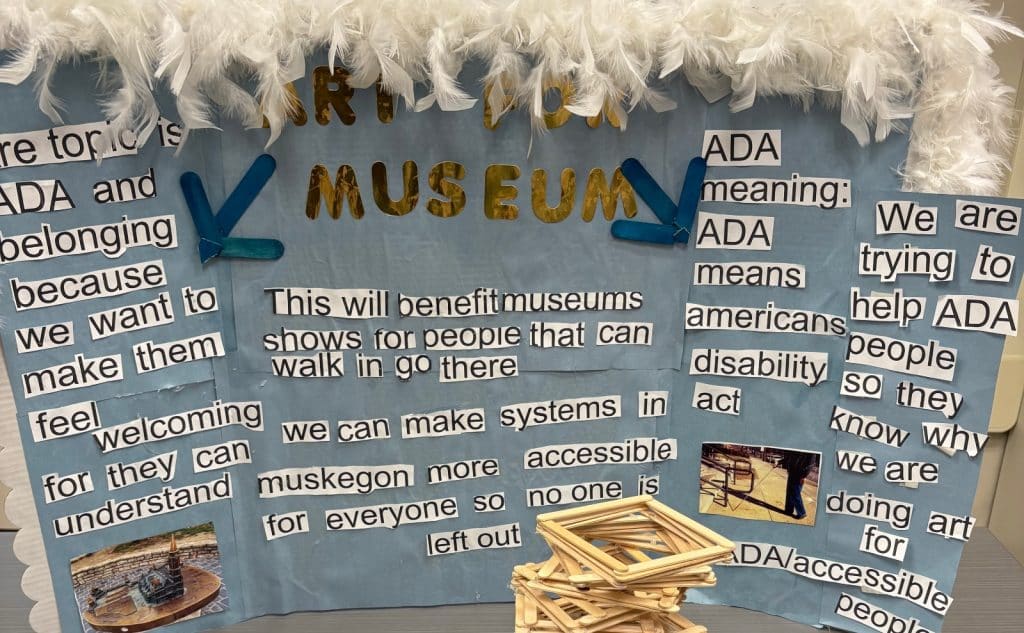

“We did a presentation on accessibility and ADA understanding,” says Childers. “What the Americans with Disabilities Act is, what it means, and how the disability symbols have evolved, from the past to what’s accepted now.”

Childers joined DNWM in August. His new role is focused on ADA accessibility and inclusion. He wants to ensure that buildings, public spaces, and redevelopment projects are designed with accessibility in mind from the start.

That work often happened behind the scenes. Childers reviewed blueprints and renderings for new construction and renovations, identifying barriers before they were built and advocating for barrier-free designs.

“It’s not just about compliance,” he says. “It’s about dignity.”

Untapped imaginations

At Reeths-Puffer, Childers wanted students to understand that accessibility isn’t fixed; it evolves as awareness grows. So after his presentation, he challenged the students to imagine what a truly inclusive world could look like. That’s where the Legos came in.

The students surprised him with what they did with the colorful blocks to solve accessibility.

“The creativity these kids had was just amazing,” Childers says. “There were no limits.”

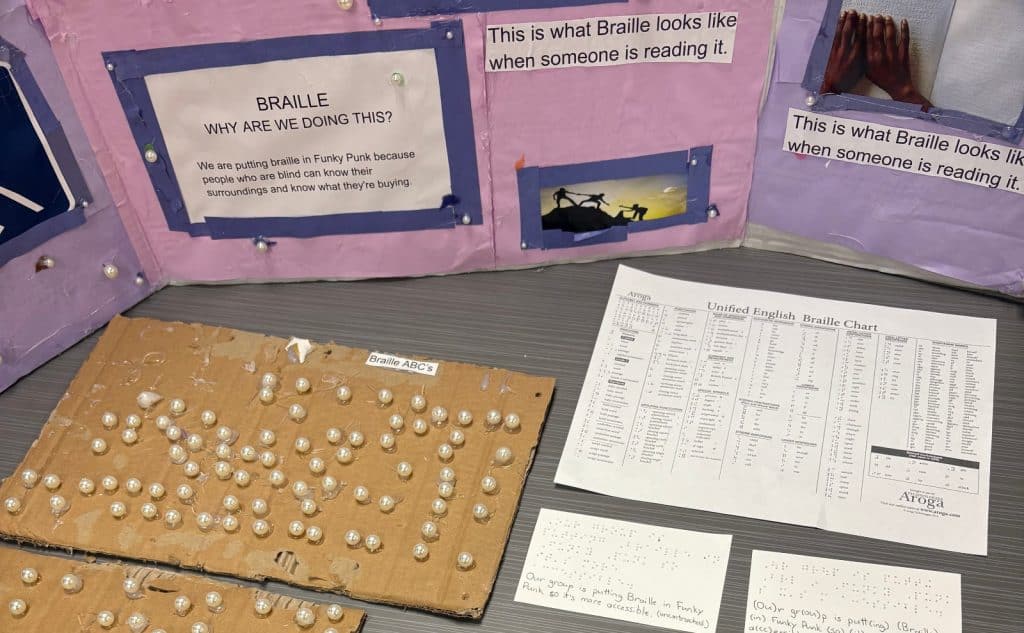

Working in small groups, students created models of accessible playgrounds and businesses, complete with wheelchair ramps, wide pathways, and even Braille signage and designated areas for service animals.

“We don’t even have parks or businesses as accessible as what these kids created with just their imaginations,” Childers says. “It really makes you think about what’s possible when people are taught to see differently.”

Moments like this reinforce Childers’ belief that inclusion is a learned practice that is most effective when introduced early.

“If we can all learn to see each other in each other’s shoes,” he says, “we can give one another more grace, accommodate each other better, and show more compassion. That’s just being human.”

Varied background

Childers’ work in accessibility began years before his role at DNWM. He started out in special education, working as a paraprofessional at Timberland Charter Academy, a K-8 school in Muskegon County.

“That experience stays with you,” he says. “It gives you perspective.”

From there, his focus expanded beyond the classroom and into neighborhoods. His career path took him to a new role as a consultant and community engagement specialist with the Muskegon County Livability Lab.

In that role, Childers helped establish neighborhood associations in Muskegon Heights, where he was born and raised. The work combined research and data with his own experience. He spent time knocking on doors and asking residents what they wanted for their community.

“It wasn’t about dropping in with a solution,” Childers says. “It was about building something together.”

That approach continues through the Muskegon Heights Neighborhood Association Council and the Muskegon Heights Strong. The latter is an initiative that Childers helps guide to bring residents together. He describes the work as being done block by block and neighborhood by neighborhood.

In those conversations, Childers often hears calls for affordable housing, better infrastructure, and increased investment. He doesn’t dismiss those concerns. Instead, he reframes them.

“How about a job where I don’t need subsidized housing?” he asks. “I’d like a piece of that dream, too.”

It’s more than a socio-economic issue.

“This isn’t a race issue. It’s a human issue,” says Childers, noting that people with disabilities often struggle more than other groups with being unemployed and finding accessible housing and transportation.

He adds that too many people are working multiple jobs and still struggling to get by, so poverty is not a lack of effort. Until people are given tools, skills, and real opportunity, Childers said, it’s hard for them to imagine a different future, let alone reach for it.

“People need to be able to see what they can accomplish if given the chance,” he says. “That’s when things change.”

Role as entrepreneur

Outside of his work in accessibility and community advocacy, Childers is also a small-business owner, balancing his role at DNWM with the growth of a wine company he launched with his family.

The business, Estelita Wines, began during the early months of the pandemic in 2020. It is named after his business partner and grandmother, Estelita “Mimi” Rankin.

Childers runs the company alongside his mother, managing it largely as a virtual operation while continuing his full-time advocacy work.

The idea took shape while he was traveling with a national nonprofit, where Childers was immersed in conversations about food systems, public health, and entrepreneurship. A key influence was a panel discussion on nutritional policy hosted by the Wellville National Nonprofit, which highlighted the intersection of healthy food access and economic opportunity.

“That conversation changed how I thought about what was possible,” Childers says.

What started as an experiment during the pandemic has grown into a national operation. Estelita Wine, sourced from a variety of fruits, is now distributed in about 30 West Michigan stores.

Childers sees the business as less about the product and more about ownership and showing what happens when people are given an opportunity to try. These are the values that he carries into his work in accessibility and community building.

In his work for DNWM, Childers wants people to see accessibility not as a technical checklist. It should be a fundamental aspect of design. Ultimately, it reflects a community’s priorities.

“When buildings are designed without accessibility in mind, it sends a message,” he says. “And when they’re designed right, it sends a different one.

By identifying barriers early, Childers says his work helps save time, money, and improve the quality of life. Just as important is what happens outside the blueprints.

The answers aren’t in quick fixes, universal solutions, or shortcuts. Meaningful change comes through consistency, presence, and conversation. Those are the key to progress, Childers believes.

“People need to know someone is listening,” he says. “That their concerns matter.”

The multi-regional Disability Inclusion series is made possible through a partnership with Centers for Independent Living organizations across West Michigan.

Photos courtesy of Marquis Childers Jr.