GVSU looks to connect its informal trail system into regional greenway

By studying these student-created footpaths through GVSU’s ravines, the university and its partners aim to deepen the understanding and connection to this cherished landscape.

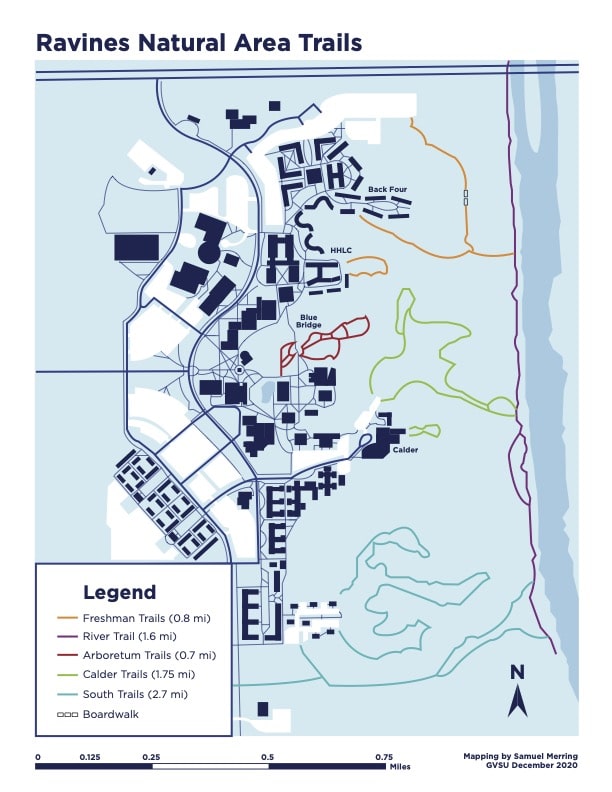

Many maps of Grand Valley State University’s Allendale campus show the ravines leading down to the Grand River as empty spaces—steep areas that existed long before the university was built. Over the years, students have created their own paths through these ravines, forming informal trails for activities like running, birdwatching, mountain biking, and studying quietly, or just finding a break from campus life.

After many years of these paths being used mainly for convenience, the university is beginning to think about what they could really mean – a way for folks on campus to be part of a larger network that connects to West Michigan’s growing system of parks and green spaces.

Trail usage at GVSU has increased by nearly 30% in just a year, according to Aaron Mowen, the director of recreation and wellness at the university. This surge has led GVSU to begin examining 14 miles of pathways along the ravines to gain insights into their ecological health, potential erosion issues, and cultural importance. The aim is straightforward yet ambitious: to transition from mere discovery to active stewardship.

“With growing use, we know we need to understand what we have,” Mowen says. “That means studying the land before we decide how to build or connect trails.”

GVSU has undertaken environmental assessments that examine erosion, invasive species, sensitive habitats, and archaeological features. Although this work is still in its early stages, it represents a significant shift in its approach: instead of letting informal paths determine how the ravines are used, the university is exploring ways to properly care for them while also responsibly inviting more people to enjoy the landscape.

And the good news for GVSU is that area partners, also engaged in advancing greenway work across the region, are paying attention.

Rethinking what a trail is for

Exploring the ravines on a crisp fall day, Mowen invited Rapid Growth to witness the stunning beauty of this ancient landscape. Each turn along the trail offered a new perspective.

However, this area is delicate. The sandy soils are prone to erosion, particularly where informal paths have been carved into the steep slopes. To accommodate more visitors without damaging the environment, careful planning and collaboration beyond the campus will be crucial.

For Mowen, the mission goes beyond conservation; it’s also about fostering connections via this trail. He envisions linking GVSU’s trails to the Grand River Greenway, a long-standing initiative to protect the land along the river and establish a continuous public trail system in West Michigan..

This connection would create new opportunities for recreation and education, allowing students to explore Ottawa County’s finest natural areas and encouraging nearby residents to engage with the campus.

“The trails shouldn’t just serve campus,” Mowen says. “They should serve the community — and the land.”

Lessons upstream

Few individuals are as familiar with this landscape as Melanie Manion, the conservation manager at Friends of Grand Rapids Parks. Before her current role, she spent several years with Ottawa County Parks, where she helped manage areas that GVSU aims to connect.

Manion thinks GVSU is taking the right approach by beginning with environmental assessments.

When Ottawa County acquired the land that would later become Grand Ravines Park, located just a short distance from the Allendale campus, some of it was still being used for farming.

Instead of letting this disturbed land become overrun with weeds, the county planted native prairie. This restoration effort created a thriving habitat and quickly became a popular spot, attracting photographers, bird enthusiasts, and families alike.

“You have woods on one side and this big, open native grassland on the other,” Manion says. “Because of that, people go there to take photos, to hike, to just enjoy it. It’s beautiful and peaceful — and that draws people into a deeper relationship with the land.”

Planners protected the steep slopes of the neighboring ravines by establishing designated viewpoints, allowing visitors to appreciate the forest’s depth while minimizing environmental impact. In an effort to create a more welcoming experience, some trails were paved to improve accessibility to the overlooks.

For Manion, these decisions reflect a simple principle.

“When I say ‘smart,’ I mean sustainable,” she says. “A smart trail protects the ecosystem, doesn’t create huge maintenance needs later (thus lowering costs over time), and is usable by as many people as possible.”

This also means being willing to change plans when necessary. For example, during the early stages of construction, the county discovered that contractor equipment had introduced Japanese knotweed, one of the most aggressive invasive plants in the world, which can even travel under pavement. As a result, the county required that all equipment be cleaned before entering sensitive areas.

“That one lesson saved years of labor and hundreds of thousands of dollars,” she says. “It was a tough way to learn, but we carry that wisdom with us.”

Opening land creates new stewards

Some people are concerned that opening new trails may degrade natural areas. Manion acknowledges this tension, noting that trails can create disturbances, but argues that careful access can actually improve ecological health.

“If land just sits there, it often degrades,” she says. “When it becomes public space, people get involved. They help remove invasives; they help care for it. That’s when the land becomes healthier.”

Trails create a sense of belonging. When people feel welcome in a place, they are more likely to advocate for it and envision themselves as part of its future.

Her strategy emphasizes long-term thinking. With climate-driven changes affecting tree health and leading to species migration, West Michigan—once recognized as Zone 5—has now been reclassified as Zone 6A. This shift illustrates the lasting impact that today’s choices will have on our future habitats.

“We’re not planning for ourselves — we’re planning for future generations,” she says.

Paths that remember

Any plans for the ravines should acknowledge the deep history of human presence in the Grand River valley. The river continues to hold significant importance for many tribal nations. Manion notes that parks nationwide are increasingly incorporating Indigenous wisdom to enhance their land management practices. She referenced the seven generations principle, which teaches that decisions made today should consider the impact on seven generations to come and honor past generations.

“Indigenous communities have been recording their history of this land longer than any of us,” she says. “Their knowledge helps us understand the river, the plants, and how people can connect to place with respect.”

In her previous position, Manion worked to establish a collaborative partnership between Ottawa County and tribal leaders during the initial planning stages, rather than waiting until after decisions were made to seek their input. The aim was to foster genuine collaboration rather than mere consultation so that knowledge could be assembled for smarter decision-making.

Slow down and listen

As more communities develop trails, Manion emphasizes an important lesson: prioritize the process by taking the time to slow down and actively listen to community needs and feedback.

“There’s often an assumption that everyone will love the idea of trails once they see a map,” she says. “But when plans are shown before listening, some people react negatively — and rebuilding trust can take years. Sometimes it never happens.”

She advocates starting discussions from curiosity rather than attempting to persuade others to adopt one’s often-narrow vision that may not reflect invaluable community knowledge.

“It really helps to begin with people’s concerns before presenting any design,” she says. “In a perfect world, you’d even ask trusted, like-minded neighbors who were once skeptical to help present information. People hear things differently when it comes from someone they relate to.”

“If people don’t feel connected, they won’t support ecological work,” Manion says. “Connecting people to nature doesn’t just help humans — it’s good for the land, too.”

This perspective redefines trail development as a relational process, influenced by trust as much as by the landscape itself.

This idea is central to the initiatives currently underway at Friends of Grand Rapids Parks. Manion points out that Friends’ Executive Director Stacy Bare has been fostering partnerships in regional trail planning, including discussions with GVSU, to ensure that both conservation efforts and community voices remain engaged throughout the process. Manion emphasizes that the current work is a testament to Stacy’s leadership and his ability to build coalitions.

The work ahead

At this stage, GVSU is engaged in listening to community feedback. The university does not yet have a timeline for trail development, and Mowen highlights the importance of ensuring that future plans align with the sustainability of both the land and the community.

“You don’t start with a map,” he says. “You start with understanding.”

When we embark on a slow and thoughtful design journey, we follow a path much like the trail itself – listening first and adjusting our course as new terrain unfolds. Collaboration becomes our guiding compass, helping us navigate together. This approach transcends mere care; it fosters lasting relationships with partners and neighbors, transforming the ravines from hidden places on campus into shared spaces of hope for Michigan’s future.

We can envision, within the design process, a trail system that seamlessly brings together leisure, conservation, cultural appreciation, and a sense of belonging. The ravines have the potential to serve as a dynamic example of this balance, where each step reminds us of our ability to care for our environment while strengthening our community connections.

In a landscape shaped by the ancient flow of water, change unfolds with purpose with each thoughtful action. In this moment, we are invited to see the ravines as more than a tranquil escape, for they now hold the power to transform into a vibrant corridor, uniting humanity with the natural world.

On the trail, we not only connect with the land but also nurture its future through the uplifting journey toward harmonious coexistence with nature. Together, whether at GVSU or any of the many trail systems of our region, we can create a path that serves as a sanctuary for life, where every moment, every step reflects our commitment to creating a thriving trail system environment for generations to come.

With support from Friends of Grand Rapids Parks, Rapid Growth Media explores the future of outdoor recreation in West Michigan. This series examines key themes such as trail expansion, rural access, regional collaboration, youth engagement, economic impact, and park conservation, highlighting the opportunities and challenges shaping the region’s outdoor spaces.

Photos by Tommy Allen